[ad_1]

And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. (Matthew 6:12)

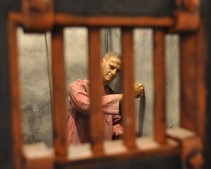

Then his lord summoned him and said to him, ‘You wicked servant! I forgave you all that debt because you besought me; and should not you have had mercy on your fellow servant, as I had mercy on you?’ And in anger his lord delivered him to the jailers, till he should pay all his debt. So also my heavenly Father will do to every one of you, if you do not forgive your brother from your heart.” (Matthew 18: 33-35)

When the Apostle Peter asks Jesus, “Lord, how often shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive him?”, Jesus replies by telling the parable of the king who wishes to settle accounts with his servants (Matthew 18:21-35). Jesus says this settling of accounts is what it will be like in the kingdom of heaven. The surprise of the parable is that the king is incredibly forgiving, canceling the enormous debt simply because the servant asks for patience from his lord. Note that the servant asks only for more time to repay, but the Lord forgives the entire debt! But that is not the end of the parable, for the story goes on with a lesson that in the same way that the Lord forgives our debts to Him, so we are to forgive those indebted to us. If we fail to forgive those indebted to us, we too will have to repay all our debts to God. Biblical scholar Nathan Eubank comments on the parable and Christ’s words that the unforgiving person will be incarcerated until he repays his entire debt. Some see this as a reference to or threat of eternal punishment.

Jesus’ warning ‘Truly I say to you, you will certainly not go out from there until you repay the last penny‘ is an illuminating parallel of 18: 34. There is no question here of a debt that is too large to repay, only that one’s entire debt must be repaid before ‘you go out from there.’ In spite of this, however, commentators still almost universally assume that verses 25-26 refer to never-ending punishment. Gundry, for instance, writes that ‘failure to make things right with a brother in the church falsifies profession of discipleship and lands a person in hell, the prison of eternally hopeless debtors…’ Yet, both here and in 18: 34 Jesus’ warning seems to indicate that imprisonment will last until the debt is paid. It is worth exploring the possibility that Matthew is saying that it is possible to repay debts from prison, that is, from Gehenna.

According to both Greek and Roman sources, debt was the commonest reason for imprisonment in antiquity, including first- century Palestine. The purpose of such imprisonment was not purely punitive but coercive. That is, incarceration was intended to compel debtors to produce any hidden funds they might have, and, should that fail, to incite friends or family to pay the ransom – that is, to pay the debt. Physical torments added further incentive. When the debt was paid prisoners were released. For modern biblical scholars the image of someone being confined until he ‘repays the last penny’ may evoke images of everlasting damnation, but Matthew’s audience would have thought first of prisons which were for the most part ‘temporary holding cells in which offenders, and these mainly debtors, endured brief stays.’

Just as debtor’s prison was intended to be a temporary means of facilitating the repayment of debt, Gehenna was sometimes thought of as a temporary place of chastisement. … Gehenna was sometimes viewed as a place where redemptive suffering takes place, a process of purification which is compared to refining metal in fire (Zechariah 13:9). . . . Second Maccabees 12 shows that there existed the belief that some kind of atonement could take place after death and prior to the resurrection well before the late first century CE. when Matthew was written. (WAGES OF CROSS-BEARING AND DEBT OF SIN, pp 59-59)

As Eubanks shows, the parable is not necessarily talking about eternal punishment for sinners, but more of a temporary purgatory for working off one’s debt before one is released into the kingdom. For us, it is a parable telling us to be merciful to others because God is merciful to us.

Biblical scholar Roberta Bondi notes:

It is often, for example, a sense of God’s forgiving presence right now, at the time of looking within ourselves, that illumines for us how far we may be from truly forgiving a person who has injured us. (TO LOVE AS GOD LOVES, p 84)

[ad_2]

Source link